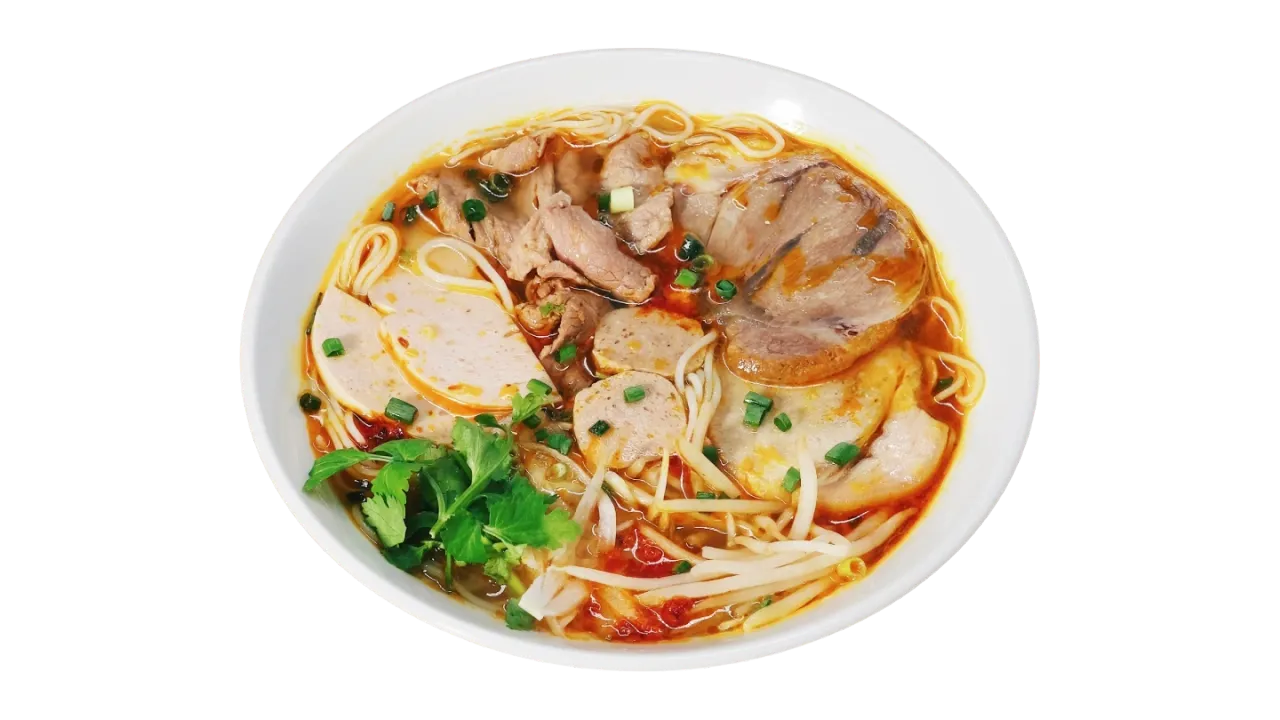

If you ever have the chance to visit the ancient capital, you will notice an interesting detail: the locals of Hue rarely call their familiar breakfast dish "Bun bo Hue". To them, it is simply "Bun bo" (beef noodles) or more specifically, "Bun bo gio heo" (beef and pork trotter noodles) [4]. The suffix "Hue" seems to be a designation added by expatriates or travelers from afar, serving as a respectful affirmation of the roots of this soulful bowl of noodles.

Today, let's join Banh Mi Xin Chao on a journey back in time to trace the origins of the dish that the late renowned chef Anthony Bourdain once proclaimed to be "the greatest soup in the world" [2]. We will discover that within this humble bowl lies a tumultuous historical journey and ceaseless culinary creativity.

The legend of the woman who "offended the gods" for the pearls of heaven

The story of Bun Bo does not begin in the gilded royal palaces, but rather stems from an incident in Co Thap village (now in Quang Dien commune). Legend has it that long ago, when people from the North followed Lord Nguyen Hoang southward to establish a new life, there was a beautiful and talented young woman who chose the trade of making vermicelli (bún) from rice instead of farming like the rest of the villagers. The locals affectionately called her Ms. Bún (Lady Noodle) [1].

Disaster struck when Co Thap village suffered crop failures for three consecutive years. Fear and jealousy led strictly traditional villagers to spread rumors that the gods were punishing them because Ms. Bún dared to take "heaven's pearls" (rice) and soak, scrub, and crush them. Under the pressure of harsh prejudice, she was forced to either quit her trade or leave the village. Determined to preserve her craft, Ms. Bun, along with five strong young men, carried their stone mortars and headed East. Upon reaching Van Cu village, exhausted but recognizing the benevolent land and the cool blue waters of the Bo River, she decided to stop and establish her livelihood there [7] [8]. From then on, the craft of Van Cu vermicelli was born, becoming the indispensable ingredient that would later form the soul of the beef noodle soup.

This story offers us a very human and modern perspective: sustainable cultural values sometimes sprout from injustice, from a fierce desire to survive, and a mindset that dares to be different, rising above the antiquated prejudices of the time.

From a sacrificial "beef stew" to the royal standard of "ten perfections, five gains"

Many cultural researchers and culinary artisans, including artisan Mai Thi Tra, believe that the predecessor of Bun Bo was actually a dish called "xáo bò" (rustic beef stew) served with sticky rice. In the old days, the cow was one of the "three sacrificial animals" (along with goat and pig) used in ritual offerings. After the ceremony, the prime cuts of meat were distributed, while the scraps, bones, and belly meat were cooked into a stew. Gradually, as the vermicelli craft developed, people replaced the sticky rice with vermicelli to be more economical and easier to eat, thus giving birth to the primitive version of Bun Bo [7].

The transformation from a rustic folk dish to a work of culinary art bears the distinct mark of Duke Dinh Vien - Nguyen Phuc Binh (the sixth son of King Gia Long). Legend has it that he was a gourmet who once organized a cooking competition for pork trotter noodles at his residence with rigorous criteria known as "thập toàn, ngũ đắc" (ten perfections, five gains) [5].

- "Thập toàn" (ten perfections) refers to ten points of perfection in both taste and form: delicious, fragrant, sweet, rich, pure, nutritious, beautiful, skillfully selected, skillfully cooked, and skillfully presented.

- "Ngũ đắc" (five gains) refers to five attainable qualities: known by all, affordable, edible by all, easy to prepare, and ingredients found locally.

It was this fastidiousness of the imperial capital that breathed a soul into the simple beef stew, turning it into the harmonious and sophisticated ensemble we enjoy today.

Yin-Yang balance in culinary philosophy

From a food science perspective, Bun Bo Hue is an excellent testament to the Yin-Yang balance—a crucial philosophy in East Asian culture. It is no coincidence that this dish has existed for hundreds of years and conquered international palates.

Beef and pork trotters provide protein and nutrients. But the magic lies in the spices. The spicy heat of chili, along with the warm fragrance of lemongrass, shallots, and pepper (Yang/Hot nature), is used to balance ingredients with "Cold" (Yin) properties like the vermicelli, fresh herbs, and the seafood elements in the fermented shrimp paste (mắm ruốc) [7] [9]. Notably, mắm ruốc not only creates a rich depth (natural Umami) but is also the decisive factor in the distinct flavor that is "unmistakable" anywhere else [6] [7].

An interesting point few notice is the evolution of the noodle strands. In Hue, authentic old-school noodle strands were typically large and round, made from molds with holes larger than the thin vermicelli found in other regions [4]. The thick strands allow the diner to feel the texture—chewy, slippery, and substantial—when combined with the soft braised beef or the fatty pork trotter.

The continuing journey of a heritage

Bun Bo Hue is not merely a breakfast dish. It is the crystallization of migration history, the intersection between Cham culture (marked by the ancient towers in Co Thap where Ms. Bún left) and Vietnamese culture, and a blend of the rustic village stew and the sophisticated intricacy of royal cuisine.

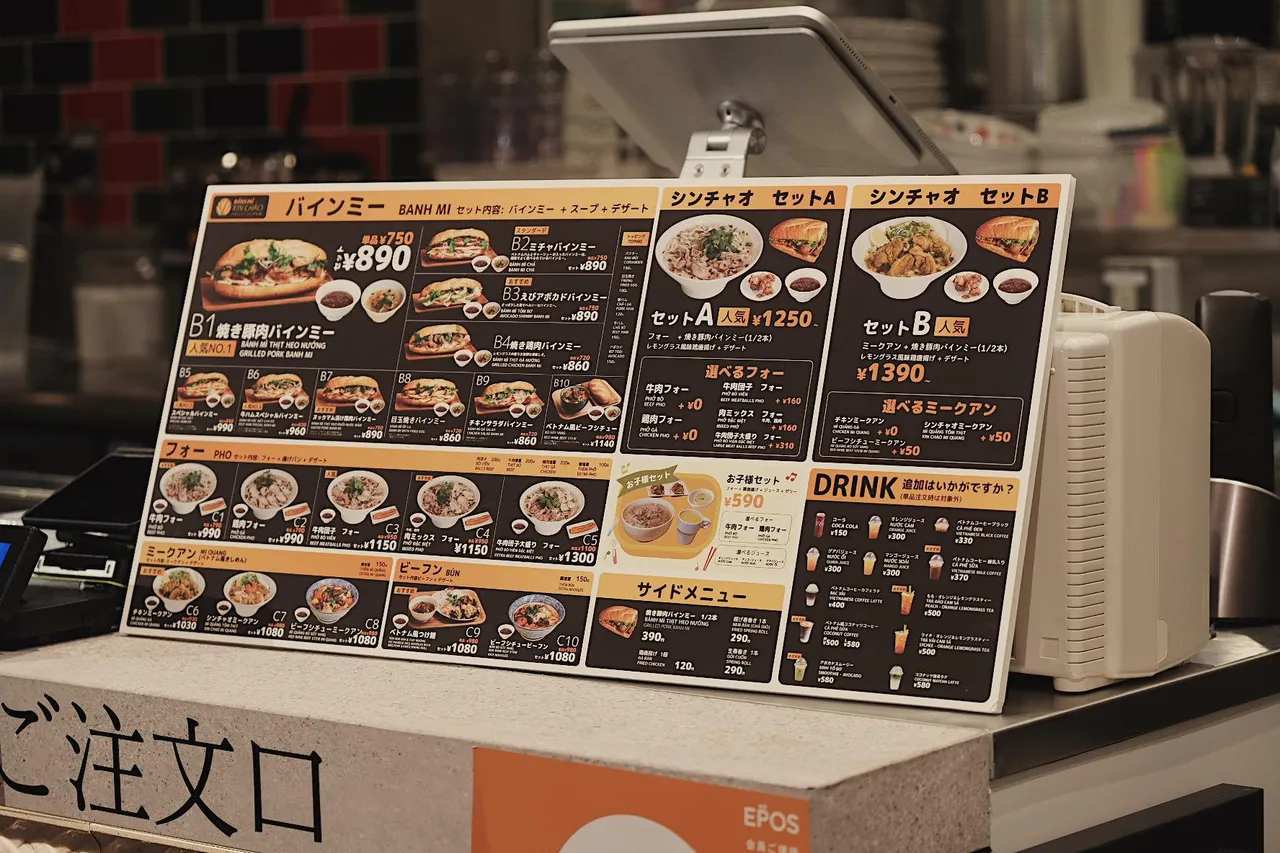

Today, although Bun Bo has followed the Vietnamese people across five continents—from Saigon and Hanoi to Tokyo or California—and has undergone many variations to suit regional tastes, its roots remain deep in the memories of Van Cu village and the cool blue Bo River.

In the next article, we will delve deeper into that 400-year-old Van Cu village to see just how elaborate the process of making "Hue standard" vermicelli is, and why it is said that without Van Cu noodles, a bowl of Bun Bo Hue loses half its soul.

References

- Bảo Kim & Quang Tám (2025, August 3). Đặc sắc làng bún hơn 500 năm tuổi. Báo Người Lao Động.https://nld.com.vn/dac-sac-lang-bun-hon-500-nam-tuoi-196250802194536604.htm

- Dan Q. Dao (2021, December 8). Anthony Bourdain's Former Assistant Laurie Woolever On His Life, Legacy, And Love For Vietnam. Vietcetera.https://vietcetera.com/en/anthony-bourdains-former-assistant-laurie-woolever-on-his-life-legacy-and-love-for-vietnam

- Khám phá Huế (n.d.). Làng nghề truyền thống Bún tươi Vân Cù. Retrieved December 28, 2025,https://khamphahue.com.vn/Van-hoa/Chi-tiet/tid/Lang-nghe-truyen-thong-Bun-tuoi-Van-Cu.html/pid/7606/cid/323

- Nguyễn Hoàng (2014, October 20). Bún bò đúng kiểu Huế: Phải vào Sài Gòn ăn mới ngon?. Thanh Niên Online.https://thanhnien.vn/bun-bo-dung-kieu-hue-phai-vao-sai-gon-an-moi-ngon-185426352.htm

- Trần Hòa (2021, March 4). Trăm năm văn hóa cố đô trong bát bún bò xứ Huế. Báo Giáo dục và Thời đại.https://giaoducthoidai.vn/tram-nam-van-hoa-co-do-trong-bat-bun-bo-xu-hue-post578075.html

- Trung Hiếu (2016, March 11). Bún bò Huế. Tạp chí điện tử Thế giới Di sản.https://thegioidisan.vn/vi/bun-bo-hue.html

- Tuấn Anh (2024, February 18). Nguồn gốc của bún bò Huế - hồn cốt cố đô. VnExpress.https://vnexpress.net/nguon-goc-cua-bun-bo-hue-hon-cot-co-do-4910854.html

- Vietnam+ (2025, February 23). Đến Huế thăm làng nghề làm bún Vân Cù có tuổi đời hơn 400 năm. VietnamPlus.https://www.vietnamplus.vn/den-hue-tham-lang-nghe-lam-bun-van-cu-co-tuoi-doi-hon-400-nam-post1013239.vnp

- VNA (2020, June 10). Hue cuisine – Typical culture of former imperial capital. VietnamPlus.https://en.vietnamplus.vn/hue-cuisine-typical-culture-of-former-imperial-capital-post181975.vnp